Read this if you’ve struggled with moderation, and if you're wanting to establish—and stick to—an optimal dose.

You're at the grocery store.

Like a pro, you shop the perimeter—veggies, fruit, protein. No processed foods. No junk. You even make it past the ice cream unscathed.

But then, as you make your way to the check-out lines, your eyes catch the deep blues and reds of the chocolate bar display (or the cracker aisle, or chips section, or whatever else your snack-crack may be).

You shrug and think, "Eff it. I can allow myself one little treat."

When you get home, you unwrap the bar and proceed to enjoy that first row. With a smile, you wrap up the rest before stashing it away. You continue your day with peace of mind, proceeding to accomplish your goals to make the world a better—no, that’s never happened.

What actually happens is, you go to your desk, you attempt to work, but all you can think about is the half-eaten chocolate bar just sitting there in the cabinet. So, you get up and pace around like a crack-fiend until you break. You eat the next row, then the next, then the next, until you’re licking the wrapper in desperation for more.

For a second, you’re all like, #noregrets. Until that moment passes and you’re like, #okfinepureregrets.

The invention of wanting

It’s incredibly frustrating.

You know your life experience would be markedly better if you could just control yourself. It always feels like moderation is totally doable, and yet it ends up being impossible.

What gives?

For the longest time, I was obsessed with finding a solution to this dilemma. And it went beyond stuff like chocolate. I could never figure out how to play video games just for an hour, or watch just one episode on Netflix, or limit myself to 20 minutes on Reddit.

Here’s what took me years to realize… years to come to terms with.

There is no solution to this dilemma.

Short of lobotomizing the reward center of your brain, you’re either going to be overtaken by dopamine-fueled impulses that’ll drive you to a binge… or you’ll have to summon and sustain super-human levels of willpower to not do what every fiber in you is begging to do.

The fantasy of one row of chocolate, one episode of Netflix, one brief dive into Reddit, followed by satiety and bliss… is exactly that—a fantasy. A fantasy that simply does not exist.

It cannot exist.

Why? Well, with the invention of chocolate came the invention of wanting chocolate.

You see, a key ingredient in chocolate is sugar. In nature, sugar is typically available only during short seasons when certain plants bear fruit. When we take a bite of something sweet, we get rewarded because of the survival benefits of sugar: calories to burn for energy.

But then what happens? A few seconds later, we find ourselves craving more.

This goes against logic. Consuming something should satisfy and quench our desire for it. It shouldn’t do the exact opposite, right? But it does. Big time.

There’s a biological reason for this. To our antiquated brains, the sensing of sugar on our tongues could only mean one thing: it’s summer. And because the summer harvest is always so short, we evolved to be compelled to take in far more calories than our immediate needs. That way the excess sugar in our blood stream, if we were lucky enough to have an excess, could be stored in our fat cells, to be consumed later in the year.

Because of this process, our ancestors were able to survive long, cold, berry-less winters. On a yearly cycle, these short periods of caloric surplus were balanced with long periods of caloric deficit. So, wanting more with each bite, not less, was a way to ensure our survival.

The problem is, you might conclude, there are no more winters—not like the ones our ancestors experienced. With cheap, processed, energy-rich foods available all year round, plus heating systems and artificial lighting, we’re living in an era of perpetual summer.

So we are compelled to eat sweets but that makes us want more, so we eat more, but then we want more, and… on a societal level, we get the obesity epidemic. And on a personal level, we get you and your ongoing struggle with moderation.

Wanting is super uncomfortable

Wanting chocolate (or sugar, more accurately) while knowing there’s more of it tucked away in the cupboard is a legitimately uncomfortable and potentially unbearable experience. It’s like resisting the urge to scratch a mosquito bite: Unsatisfied desires are agonizing.

So—and this is key—you end up eating row number two of the chocolate bar, or watching the next Netflix episode or YouTube video, not because you’re chasing the next hit of pleasure, but because you are chasing relief.

You are simply experiencing the discomfort of wanting more, and consuming more is the only way to make it go away.

So, the “pleasure” you get from eating more sugar or thumbing down a social media feed is the same “pleasure” you get from scratching a mosquito bite. You might say, "Aahhhh... ooooh.. that feels so good," but is it really pleasure, or is it just the bliss of returning to a normal state without an unbearable itch?¹

The problem is that now the supply of vices is virtually endless. And so the cycles of craving and relief have no end. On the contrary, the cycle only amplifies as bad feelings like guilt, stress, and regret begin to seep in. Before we know it, we've kickstarted that vicious Vice Feedback Loop and we're tumbling our way down into a binge.

The Real Choice You’re Making

What I’ve come to realize is this: When I stand in front of the snack aisle, or, say, when I contemplate opening the YouTube or TikTok app, I’ve been asking myself the wrong question.

It's not, “How can I moderate my vices?”

It’s, “What choice am I really making here? What am I about to experience? What choice do I make, knowing that if I decide to indulge in a small dose, there is going to be a great amount of discomfort generated through wanting more of it?”

With this frame of mind, my choices are therefore to:

- Fully abstain, then miss out on what seems—at least to my primitive and notoriously foolish brain—like a good way to feel pleasure and enjoy life.

- Attempt moderation, then experience the intense discomfort of craving more than I committed to.

- Just go with the flow, then experience the pain and regret of overdoing it, along with the hidden and delayed effects of heightened Procrastination Inducing Symptoms.

I’m not pushing one option over the others. And I don’t have a miraculous, pain-free, fourth option to sustain moderation that’ll make this book sell a million copies.

A year or two ago, I might have been adamant about option 1. I would have said that the only way is to go ZERO vices… It’s full abstinence or nothing!

But even that path can be argued as a net negative. I mean, there isn’t much redeeming about, say, cigarette smoke, but there can be bliss in savoring a few premium squares of chocolate, enjoying the experience of an immersive video game, watching an engaging YouTube video, or whatever else floats your boat.

I just can’t blame you for hesitating to throw out the baby—YouTube's treasure trove of insightful content, learning tutorials, and "how-to’s"—with the bathwater—the endless sea of gratifying but ultimately vapid content.

But when any indulgence in a vice comes to an end, there will be pain. There must be pain—that’s just how we’re wired.

The Complexities of Life

This is life. And life can be tricky. Messy, even.

It’s super easy for me to talk about vices as if they’re a single entity—a uniform and ubiquitous addictive pill that’s got everyone hooked like the Soma drug doled out in Aldous Huxley’s A Brave New World.

But vices don’t work like that. They’re not black and white. So, when it comes to moderation and our goal of living the best life possible, we're left with two basic questions:

- Under which conditions is it “okay” to indulge in a vice? And, if it is okay, how much is best? In other words, what should I commit to in terms of moderation?

- How can I get myself to stick with this commitment?

For question 2, you'll need the right combination of environmental fixes like content blockers, mindfulness based practices, and systems. You'll also need to test and refine these using an iterative approach. Basically, you'll need everything I'll throw with the Habit Reframe Method. But it can be done. If you get really systematic about it, moderation is indeed possible. I promise.

So let's first address question 1. Let's establish the “Optimal Dose” for each of your vices.

Your Vice Consumption Curves

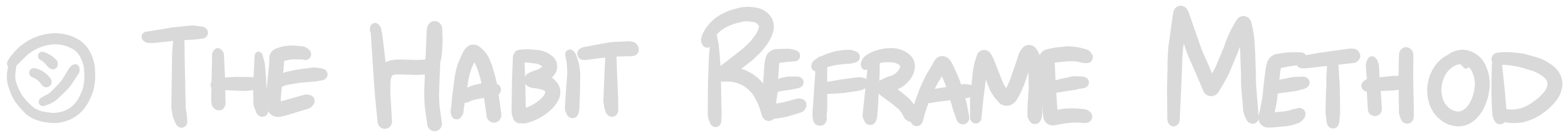

Let's consider a curve in which the x-axis is a measure of how much vices you are consuming on a daily basis. The y-axis is the effect this amount of vices has on you, i.e. the VID symptoms you experience, your ability to be productive, and your overall life satisfaction. It might look something like this:

Let's use it to resolve the question: Under which conditions is it okay to indulge in a vice... and if it's okay, how much is best?

Let's start with the 'how much' bit.

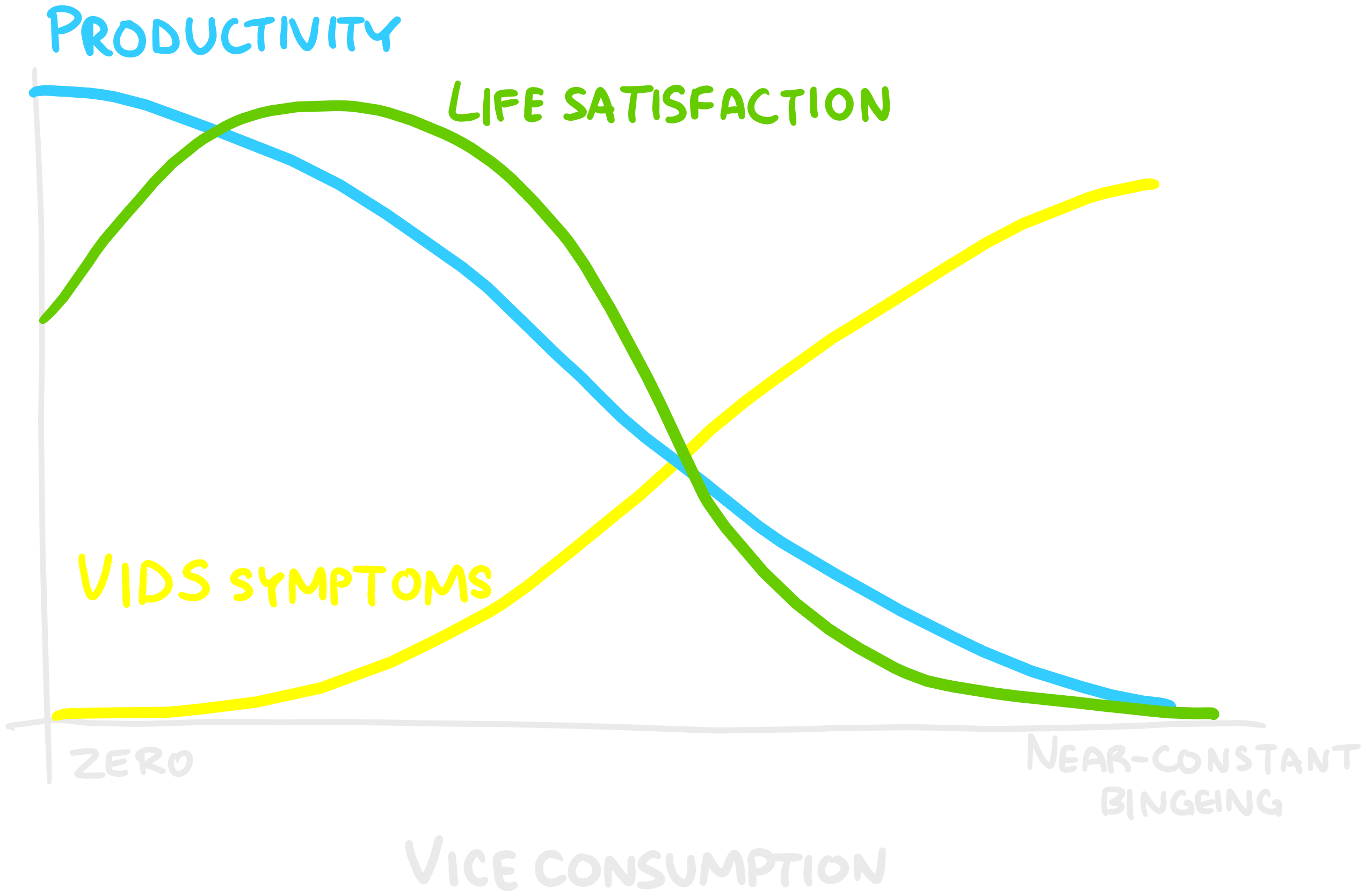

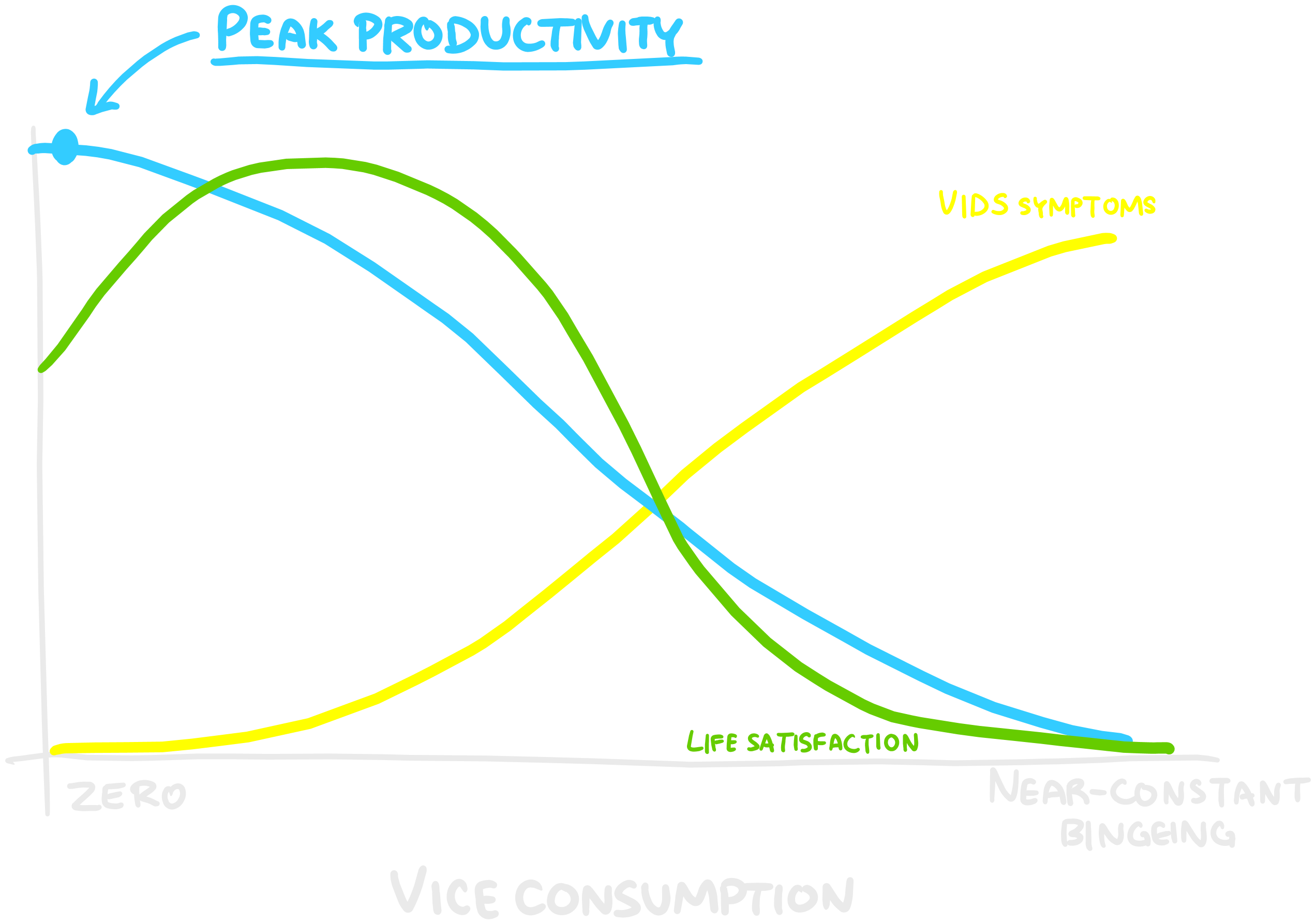

It really depends. What is your priority at the moment? Is it maxed out productivity and output? Or is it maximizing your overall life satisfaction?

If, say, you want to get a business or a creative pursuit off the ground as soon as possible, you'll need to limit your dose of vices to the bare minimum to hit peak productivity.

If, however, you want something a little more balanced and perhaps more sustainable over the long term, opt for a low but still significantly moderated amount of vice. This will max out your overall life satisfaction score.

If, however, you want something a little more balanced and perhaps more sustainable over the long term, opt for a low but still significantly moderated amount of vice. This will max out your overall life satisfaction score.

Like I said, it depends on your goals, timelines, and priorities.

Either way, you would then set details of that consumption level as an “optimal dose” within the rules part of your North Star doc.

-+-+-

Let's dive into a specific example: my own situation.

Currently (at the time of writing), I'm focused intently on releasing this program. This means my top priority is enhancing my concentration and writing efficiency. I aim to harness maximum motivation and minimize time wastage.

At the same time, I like being in the loop with the world around me. Sure, in the past, I've become obsessed with the news and conversations around it, but if moderated and well curated, such a vice does add significant value to my life.

So, on most mornings, I listen to a 10-minute CBC podcast summarizing yesterday's events. On Saturdays, my ritual involves watching a curated list of YouTube videos—ranging from late-night show rants to content from favorite YouTubers—while relaxing on the couch with breakfast. It's a fun little routine that, okay, might result in a small bump in VIDS symptoms, but it’s fairly insignificant, and, to me, it's entirely worth that cost.

Maybe when I'm done with the book and I have some more free time, I might carve out an hour or two at night to play some video games. Or maybe I'll go back to watching an episode of something on Netflix with the wife over weekday dinners.

I haven't decided yet. All I know is that I will try stuff out until I find what works; what yields my ideal balance between productivity and life satisfaction.

'Why' not 'What'

I just want to add quick word about the first part of the question from before: Under which conditions is it okay to indulge in a vice?

For this, all you need to know and remember, is this mantra:

It's not about what you do. It's about why you're doing it and what effect it has on you.

I'll write it again because it really needs to be branded onto your brain.

It's not about what you do. It's about why you're doing it and what effect it has on you.

Let's unpack it using some examples.

Do you have a good 'why'?

Are you opening YouTube because your favorite creator just released a new video and you're excited to watch it over your lunch break? ← that's a good 'why'.

Or are you indulging in that same video because you just received a critical email from your boss and you've reflexively opened YouTube to escape from the ill feelings? ← that's a bad 'why'.

How about...

Are you eating some cake because it's your brother's birthday, and your mom made her epic double chocolate cake? ← that's a good 'why'.

Or are you eating some cake because it's Susan in accounting's birthday and there's a half-eaten cake from Costco sitting in the breakroom and it's 2 pm on a Wednesday and you're bored, a little stressed and irritable, and you have a sudden craving for sugar ← that's a bad 'why'.

It's not about the ‘what’—in both examples, the vices are similar—but the ‘why’ behind the vice that's the deciding factor. In both 'good' cases, there's a specific circumstance surrounding the indulgence. Context matters.

So, an easy way to know if your 'why' is probably lacking is if the temptation is a random occurrence—if there's some triggering event that immediately preceded it.

Are you okay with the effect it'll have on you?

The eventual effects of your vices, both immediate and eventual, are equally important to consider.

Most ex-alcoholics, for example, are very strict about their sobriety. One drink, no matter how small or justified, is always one drink too many. They can have the best 'why' imaginable—C’mon, it's your wedding! Here, just enjoy one flute of champagne with all the guests—yet it's the effect of even a minimal amount that can spell trouble and derail their entire recovery.

But we aren't dealing with Tier-1 vices here, so maybe you’re perfectly capable and content with enjoying three or four YouTube videos every few nights, selecting vids on a few niche topics you find engaging and useful. Sure, it comes with a dose of discomfort once it ends, and sure it does result in a slight reduction in your motivation levels, but this is a price you're willing to pay.

Or perhaps, you've tried to moderate yourself around potato chips, but you find it just impossible. So you commit to stop buying and bringing bags home—but you give yourself permission to indulge at the rare house party. You've made peace with the reality that you just can't moderate. It sucks, but that's okay.[

In short, there really is no such thing as a universally 'good' or 'bad' vice. What matters is why you are indulging and what effect that will have on you. So here's that soundbite once again. When it comes to vices...

It's not about what you do. It's about why you're doing it and what effect it has on you.